Self-portrait of the Painter Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez

31.7.2021

The areas of Calabria where the Spanish took root most were, in the past, those that were united to the crown of Spain, such as the whole of southern Italy, where Spanish rule lasted for four hundred years in two different eras, from 1442 to 1707 and from 1734 to 1859.

The least important cultural legacy is certainly the food and wine one, the most important is the language and some traits of good manners and particularly hospitable customs of the Calabrian people.

Already in the second half of the thirteenth century, as a result of the Sicily Vespers revolution, many Catalans (Spaniards from Catalonia, the region of Barcelona) joined the mercenary army that was then formed in Italy. Following the influx of these mercenaries, which should not have been small, a first group of Spaniards was formed who were pressing on the borders of the South, if already in 1305 Roberto d’Angiò entered Florence with a gang of three hundred Aragonese knights and Catalans.

It was the conflict with the Spaniards of Aragon that strengthened the presence of this population in Calabria and in the South of Italy. Already at the time of Charles II (1285-1309), predecessor of Robert of Anjou, also due to the great economic and mercantile power and prestige that the city of Barcelona had acquired, the Catalans had been allowed to have their “Consuls“. In fact, it is no mystery that the so-called Rua Catalana in Naples dates back to this era, a street so called because it was inhabited by Catalans, especially merchants, who settled in the capital in those years.

After a long war, which ended with the victory of Alfonso I (V of Aragon) and with the expulsion of Renato d’Angiò, in 1442 the Angevins left southern Italy giving way to the Aragonese dynasty. Alfonso I of Aragon was one of the main promoters of the culture of the Renaissance, and loved to surround himself with Italian enlightened people with whom he discussed literature and philosophy. It was he who encouraged the immigration of Catalan Spaniards. The cultural climate promoted during the reign of Alfonso was characterized by the establishment in 1443 of the Accademia Alfonsina, the first academy in Italy, which was later called Pontaniana. Alfonso I never learned Italian well, but he always continued to write and speak in Catalan and especially in Castilian, since he was the son of a Castilian prince and had been raised at the court of Henry III.

During the reign of this sovereign, there was a high Spanish immigration, similar to that which had already occurred in Sicily, and much more consistent than that which occurred at the time of the court of Robert of Anjou.

FAMILY TIES AND SPANISH FEUDS

The new immigrants soon formed kinship ties with the families of the kingdom which also included Calabria: entire families settled in the Calabrian region acquiring fiefs and kin, many other Spaniards were employed in the administration, and numerous were also the prelates who came from Spain, together with peasants, artisans, employees, shopkeepers, as evidenced by the coupons of the royal treasury.

The nobles of the time were, as mentioned, mostly Catalans and Catalans were entrusted with the most important posts in the administration of the kingdom. Such an influx of Spaniards, on the one hand, strengthened Calabrian feudality, which had already undergone a strong boost during the Angevin domination, but also the mixing of the local language with Spanish. With Alfonso I the language of the court and of the chancellery became Catalan and so until 1480. Since then the influence of Spanish in the social life of southern Italy was evident in the parties and entertainment, in the fascinating and overwhelming gallantry of the costume, in the show of clothes and mounts.

At his court all the vernacular literature was in Castilian, since, the king ignoring the Italian language, he never encouraged indigenous literary production; In fact, many poets and writers followed him from Spain, who, in some cases, came into contact with our humanists.

In fact, literature in the Italian vernacular was not part of the entertainment of the court of the time, largely Spanish, which was colonized by the Hispanic tradition, until the influence was moderated by new historical facts. In fact, with the death of Alfonso I in 1458, the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily returned to divide and in Calabria the son of Alfonso, Ferrante d’Aragona, ascended the throne. Well, with the division of the kingdom the migratory flow from Spain slowed down, and indeed in some cases many of those who had followed Alfonso in the new conquered lands returned to Spain.

Perhaps it was also that Ferrante following the advice of his father on the verge of death, who would have recommended that he remove all the Aragonese and Catalans from himself and seek the support of the Italians, that he sought the support of the local people more than he had done in the past the same father and the importance of the Catalans was thus reduced.

During his reign, the Italianisation of the Aragonese grew considerably, and not infrequently the local nobles entered the administration and were also the king’s ministers.

However, the Spanish element did not regress to the point of definitively leaving everyday life, both for social and dynastic ties that still very closely linked the city to the Spanish language and culture.

The Spanish treasury coupons continued to be drawn up in Catalan for many years, just as Catalan and Castilian remained the languages of the court. Although Ferrante was not, like his father, a lover of literature, Spanish literature did not completely disappear from the culture of the time, as evidenced by the large number of Spanish poetry books from the libraries of the barons of the time.

The Spanish in the south not only fascinated the population for their gallantry and their courteous ways, they also introduced very resistant culinary traditions. The spicy Calabrian “sopressata” is very similar to the Catalan “sopressada“, for those who have the opportunity to take a look to this in Figuerez (near Girona) or in Barcelona at a traditional Spanish grocery.

THE SPANISH LANGUAGE IN THE CALABRIAN DIALECT

Even when in 1502, at the end of the struggles between the Spanish and the French for the lands of southern Italy, Naples and a large part of southern Italy was annexed to the reign of Ferdinand the Catholic and the viceroy was established, the numerous viceroys who succeeded each other, for almost two centuries, until the end of the following century, they rarely abandoned their mother tongue during their short stay and surrounded themselves with a court of their compatriots; this meant that until the beginning of the eighteenth century the Spanish language was part of everyday life, making its influence felt both in the context of social and cultural customs.

In these years, the Spanish of the time remained the language of the court and of the chancellery, but not the one in which the laws were promulgated (which were drafted in Spanish and Catalan only in Sardinia), for which Italian was used, although it existed the custom of kings and viceroys to have you insert formulas in Spanish.

Among the upper classes of society, the wealthy often tried their hand at speaking the Spanish language, considering this behavior a sign of affection and loyalty towards their rulers.

During the short Austrian viceroyalty (1707-1733), Spanish remained the official language, and with the restoration of the Spanish monarchy with Charles III, the use of Castilian was strengthened as the language of the chancellery, in which it was used equally with the Italian.

Charles III, although born of a French and an Italian, preferred to speak Castilian; his court was in fact frequented by numerous soldiers and employees who had arrived from Spain, and by gentlemen who had spent the years of Austrian rule in Spain, fighting alongside Philip V.

During the years of Bourbon rule, this tradition gradually waned, as contacts between the Spaniards and the mother country became more and more sparse and the Spanish immigration to Italy became more and more contained.

The education policy of the Bourbons contributed to the spread of the teaching of Italian and, in the wake of a trend that was taking hold throughout Europe in the eighteenth century, the French language made its way to the detriment of Spanish.

Nevertheless, the linguistic traces that almost four centuries of Spanish domination in the whole of southern Italy have left in the local dialect are numerous and very interesting.

THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA AS A TIE BETWEEN SPAIN AND CALABRIA

Towards the end of the seventeenth century, Calabria flourished in its trade towards the rest of Europe, thanks to the Spanish presence.

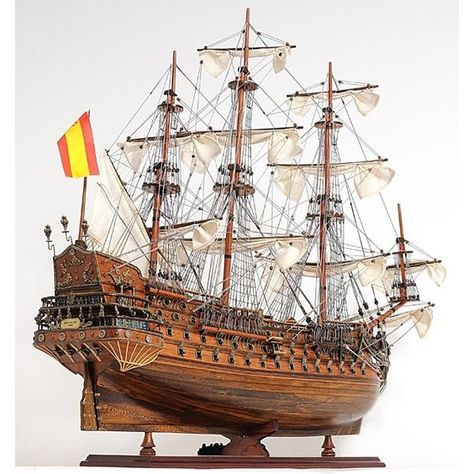

The condition of the coasts had not allowed the creation of large ports, also because the Spanish government had prohibited the sailors from the long course and the handling of large ships, however the maritime trade found its implementation thanks to the presence of numerous landings that favored transshipment and cabotage. The Calabrians became skilled sea transporters and, despite the difficulties mentioned above, the merchants of Scilla, for example, managed to establish relations with Venice and Trieste, and from those ports the exchanges continued for regions such as the Tyrol, the Istria and Dalmatia, while the sailors of Parghelia, gathered since 1692 in a cooperative society of mutual assistance called “Monte delli marinari di Parghelia“, carried out maritime trade outside the borders of the Kingdom.

The Spanish monarchy continued to build a bureaucratic structure, to give a modern organization to the Kingdom, and the demography, productivity, trade and the whole economy expanded; the already rigid and poorly articulated social structure was enriched with the emergence of new classes and a bourgeoisie.

In Calabria, therefore, the advances linked to maritime trade, on the one hand, historically unite forever, across the Mediterranean, the great Spanish and Calabrian civilizations, – on the other hand, these advances are modest during the Spanish presence, if one thinks of the gigantic steps forward that are being made towards a rapid start of political, economic and social renewal in the other European states and in central-northern Italy itself.

The Calabrian South, in fact, remains linked in those centuries of Spanish presence, to the slowness of an evolution, which through the plague of misery, faces the serious problems of the continuous social disintegration, malaria, the inclement climate and fragility of the society.

Throughout the seventeenth century, the history of Calabria was nothing more than a succession of banditry episodes, of Turkish pirate incursions, of city fights against corrupt administration and nobles reaction; and it will be necessary to wait until 1647 and the Masaniello revolution to experience a widespread attempt to achieve a political and administrative order different from that imposed by the Spanish viceroys and their dishonest provincial representatives.

However, overall the historical action carried out during two centuries by Spain in Naples was of exceptional importance and took the form of laying the foundations of the modern state in the South, that is, in the effort it made there to organize the same type of centralized and absolutist power. which distinguishes the Western European states of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. When the events of international politics made Spain move away from Naples in 1707 and allowed a short period of subjection of the Kingdom from the Viennese branch of the Habsburg dynasty, which in 1734 will lead to the restoration of Neapolitan independence – it will be seen that the South, even with all the age-old problems of disintegration, poverty and backwardness that afflict its political-social life and the economy, is, however, a country that is anything but poor in internal energies: a country that, within a few decades, will be able to face a profound effort of renewal and to express a culture and a political staff of European importance, proving that two centuries of hard labor in the shadow of the throne of a foreign dynasty had not passed in vain and that the Kingdom of 1734 was not more neither that of 1501 nor that of 1647/48.

A DEEP LINK WITH SPAIN: GOOD FRIDAY IN DAVOLI AND “A ‘NACA”

There is a religious rite that has been handed down in Davoli since the seventeenth century and is absolutely a legacy of the Spanish domination. We are talking about Holy Week, the week preceding the Resurrection of our Lord after having lived the Passion. With Good Friday all the towns and villages of Calabria carry on the rites that came to us from the Spanish “potentiores” during their domination …

Since the seventeenth century the small but suggestive Borgo di Davoli is preparing to live this exciting and little known tradition with a long preparation that lasts weeks. In the weeks before, it is the young people of the town who gather where possible to create their works of art: the fir trees loaded with rudimentary lights called “the lampiune”. Bringing the fir tree for a young man from Davoli is a really exciting thing to try at least once in a lifetime. Each light that shines in the night could represent the light of our soul that is freed from sin with the Resurrection of Christ. There are dozens of fir trees that are prepared in advance to accompany the procession of the dead Christ.

But let’s get into the heart of the tradition, the faithful gather before 22.00 at the Church of San Pietro to prepare for this particular procession defined: a naca. It is not difficult to guess the etymology of the name “naca” probably derives from the dialect and in particular from the verb “annacare” which means to move while swinging; Indeed, the rites of Spanish origin then took the Calabrian terms as in this case. However, someone thinks that the dialect word derives from the Greek nachè, which means cradle, in which the body of Jesus rests. Both etimologies can be taken into consideration!

The silent and sad funeral procession is composed to cross the village enveloped by the night, the statues of the dead Christ and the Addolorata parade in mourning always manage to reunite many people year after year. The notes of the funeral march and the gaunt rhythm of the drum and trumpet mark the pained step of the faithful, in memory of the Via Crucis of Christ. Immediately after, the bearers of these fir trees full of lights and with a swinging trend are placed. The procession starts with the sound that warn the faithful that the naca goes out through the streets of Davoli, it passes through the parishes of Santa Barbara and Santa Caterina, as well as in front of the various Calvaries scattered among the different areas of the village. Faith and legend come together for this event!

Many legends handed down by the elderly tells that they were used as torches some spontaneous plants called “varvasche” and one year the procession took place during a stormy night; the storm was so strong that it damaged the statue and the torches. A few lights remained on and were collected and placed on a fir tree found along the way. From that moment on, the custom of hanging street lamps on fir trees would have arisen “.

The feast of “Naca”, concluding his charismatic journey and returning to the Church of San Pietro, can give us the emotional sensation that Spain lives yet in Calabria, a sensation difficult to forget every year…a real Spanish tradition!